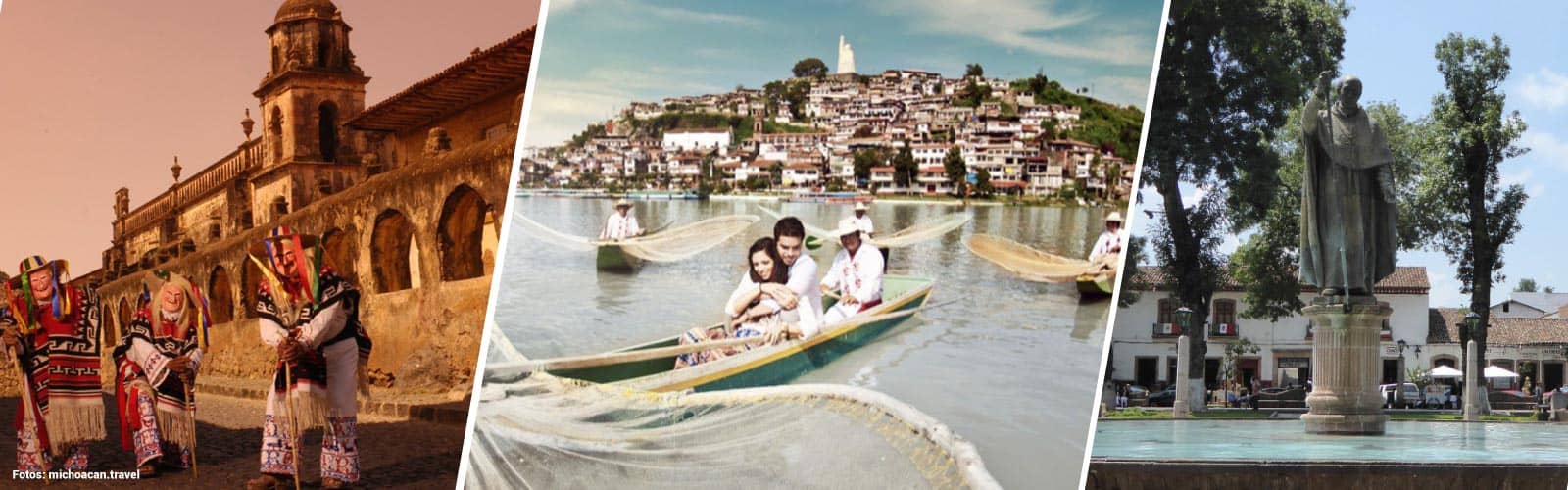

Paztcuaro and surroundings

A LITTLE HISTORY…

– The son of the last Purépecha ruler Tanganxoan II, Don Antonio de Huitzimengari left his Palace as a legacy for the indigenous communities of Lake Pátzcuaro. Nowadays Huitzimengari Palace hosts an ongoing exhibition of the renowned handicrafts produced by the Purépecha, and the building continues to be an important part of their cultural heritage.

The Museum of Art and Popular Industry is located in the old San Nicolás School, which was the first State School charged with instructing indigenous, Spanish and mestizos peoples. Among other architectural details include a floor made from a mosaic of bones, ceramic tile and stones, and a traditional Michoacán kitchen. There are also a wide and impressive variety of handicrafts.

Today, foundations of ancient pyramids known as “cues” still stand in some of the patios in colonial houses and at the back of the Museum of Art and Popular Industries.

– Historians maintain that Vasco de Quiroga (an auditor of the Spanish Crown and bishop of Michoacan) “taught” the inhabitants of Lake Pátzcuaro how to make handicrafts. However, even before the arrival of the Purépecha, the ancient villagers of Lake Pátzcuaro made handicrafts and pottery and farmed and fished around the lake. Once the migrant Purépecha arrived in the region, a new culture emerged that had a particular architectural style and whose people exhibited exceptional skills in metalwork, ceramics, and trade. The inhabitants of Pátzcuaro established a fine handiwork tradition well before the colonial period!

Pátzcuaro, the ancient capital of the Purépecha Indians in the time of Caltzontzin (King) Tariácuri, Pátzcuaro, known as a center of indigenous temples, is a magical and unusual place. Since its remotest times, its inhabitants said that the door where the gods ascend and descend to heaven is found here.

A large part of the historic center is built on top of an important indigenous ceremonial center and much of it is made with the stone taken from this site. This includes the Basilica of the Virgin of Health, the old Saint Nicholas college and numerous houses and churches. Pátzcuaro lies at 2174 meters above sea level (7132 feet), close to the Lake that bears its name, and has an annual temperature of 14 to 20 degrees Celsius (57 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit). Days are sunny and warm, nights are cool in the summer and chilly in the winter.

– P’urépechas King Tariácuri used to honor humans who had been sacrificed in religious rites by washing their bones in a waterhole in the center of Pátzcuaro. Ever since, local people have believed that the Devil himself haunts the waterhole to scare away women who come for water. This is why Vasco de Quiroga had La Pila de San Miguel built (Font of San Miguel).

– At Tzintzuntzan, 17 km (10 miles) from Pátzcuaro, you can visit the striking atrium of the beautiful church and enjoy the olive groves. During the colonial period, growing olive trees was forbidden by the Spanish Crown so as to eliminate potential competitors to Spanish olive production.

– Pátzcuaro was the capital of the Purépecha Empire during the rule of King Tariacuri (Calzonsin Tariacuri). When he died the kingdom was divided into three, and its capital cities were called Ihuatzio, Tzintzuntzan and Pátzcuaro. In all three, visitors can see the historic ruins of ancient pyramids. By 1450, Tzitzipandácuare came to power in Tzintzuntzan (which means place of the humming birds), followed by Zuangua, and then Tanganxoan.

In 1522 Cristobal de Olid, one of Hernán Cortés ‘s commanders, arrived in Tzintzuntzan and began the conquest of the Purépecha Empire. The Purépechas (also called Tarascos by the invaders) were victims of a bloody repression under Nuño de Guzmán´ s command. He murdered King Tanganxoan II.

When Don Vasco de Quiroga arrived in Pátzcuaro during the XVI Century, the town regained its long lost importance and flourished as the capital city of Michoacán in 1544. When Don Vasco died, his influence diminished and Valladolid (Morelia) located 45 km (28 miles) away, became the new capital. It was named Morelia in memory of José María Teclo Morelos y Pavón.

During Mexico’s struggle for Independence, the daughter of a wealthy merchant, Gertrudis Bocanegra de Lazo de la Vega, sided with the rebels and she, her husband and her son lost their lives. A statue to her memory is found in the Plaza Chica (small square) or Plaza Gertrudis Bocanegra.